Generative AI

Introduction

On November 30, 2022, OpenAI launched ChatGPT, a service that catapulted Generative Artificial Intelligence (Generative AI) from research labs into the daily lives of millions. This launch fundamentally changed user expectations regarding how applications and the web should function. Furthermore, the accompanying Application Programming Interface (API) gave software developers a powerful tool to make their applications significantly smarter.

Generative AI is a specialized field that focuses on processing and generating human-understandable content, including text, source code, images, videos, speech, and music. Large Language Models (LLMs) represent a significant component of this field. Trained on vast amounts of textual data, LLMs interpret and generate natural language, expanding software architecture by enabling developers to process human language effectively for the first time. Recently, Generative AI features have been integrated into established applications, including Windows, Office, and Photoshop.

As Generative AI becomes increasingly widespread, this chapter examines its emerging trends on the web. Specifically, it focuses on the use of local Generative AI, enabled by “Built-in AI” and “Bring Your Own AI” approaches, the discoverability of Generative AI content via llms.txt, and the impact of Generative AI on content creation and source code (AI fingerprints).

Data sources

This chapter uses not only the dataset of HTTP Archive, but also npm download statistics, and data provided by Chrome Platform Status and other researchers.

Unless otherwise noted, we refer to the July 2025 crawl of the HTTP Archive, as described in Methodology. For detecting API adoption, we scanned websites for the presence of the specific API calls in code. Note that this only indicates their occurrence, but not necessarily actual usage during runtime. Usage data from Chrome Platform Status always refers to the percentage of Google Chrome page loads that use a certain API at least once, across all release channels and platforms.

Technology overview

In this section, we will explain the difference between cloud-based and local AI models, discuss the pros and cons of these approaches, and then examine local technologies in detail.

Cloud versus local

Most people use Generative AI through cloud services such as OpenAI, Microsoft Foundry, AWS Bedrock, Google Cloud AI, or the DeepSeek Platform. Because these providers have access to immense computational resources and storage capacity, they offer several key advantages:

- High-quality responses: The models are extremely capable and powerful.

- Fast inference times: Responses are generated quickly on powerful servers.

- Minimal data transfer: Only input and output data need to be transmitted, not the entire AI model.

- Hardware independence: It works regardless of the client’s hardware and computing resources.

However, cloud-based models also have their drawbacks:

- Connectivity: They require a stable internet connection.

- Reliability: They are subject to network latency, server availability, and capacity limits.

- Privacy: Data must be transferred to the cloud service, which raises potential privacy concerns. It is often unclear if user data is being used to train future model iterations.

- Cost: They usually require a subscription or API usage fees, so website authors often have to pay for the inference.

Local AI technologies

The limitations of cloud-based systems can be addressed by migrating inference to the client via local AI technologies, referred to as Web AI. Since models are downloaded to the user’s system, their weights (internal model parameters) cannot be kept a secret. As a result, this approach is mostly used in combination with open-weight models, which are typically less powerful than their commercial, cloud-based, closed-weight counterparts. According to Epoch AI, open-weight models lag behind state-of-the-art by around three months on average.

The Web Machine Learning Community Group and Working Group of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) are actively standardizing this shift to make AI a “first-class web citizen.” This effort follows two primary architectural directions: Bring Your Own AI and Built-in AI.

Bring Your Own AI

In the Bring Your Own AI (BYOAI) approach, the developer is responsible for shipping the model to the user. The web application downloads a specific model binary and executes it using low-level APIs on local hardware. This allows running highly specialized models, tailored to the use case, but also requires significant bandwidth.

There are three processing units that can be used to run AI inference locally:

- Central Processing Unit (CPU): Responds quickly, ideal for low-latency AI workloads.

- Graphics Processing Unit (GPU): High throughput, ideal for AI-accelerated digital content creation.

- Neural Processing Unit (NPU) or Tensor Processing Unit (TPU): Low power, ideal for sustained AI workloads and AI offload for battery life.

The three key APIs that facilitate local AI inference are WebAssembly (CPU), WebGPU (GPU), and WebNN (CPU, GPU, and NPU).

It is essential to note that the use of WebAssembly and WebGPU does not confirm AI activity; these are general-purpose APIs frequently utilized for tasks such as complex calculations, 3D visualizations, or gaming.

WebAssembly

WebAssembly acts as the bytecode for the web. Code written in various programming languages, including C++ and Rust, can be compiled into WebAssembly. It enables developers to write optimized, high-performance code that is executed by the browser’s scripting engine on the user’s CPU.

WebAssembly has broad browser support, being implemented in all relevant browser engines since 2017.

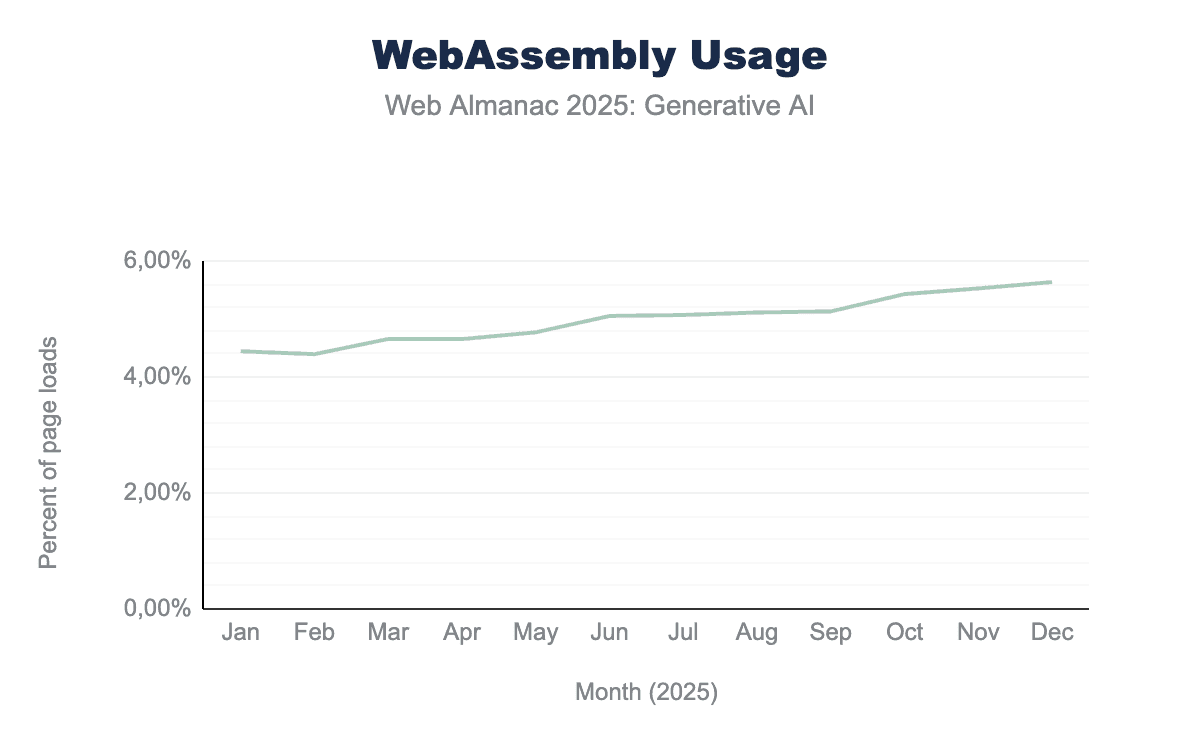

According to Chrome Platform Status data, the usage of WebAssembly experienced 27% linear growth from being active on 4.44% of page loads in January 2025, and 5.64% in December 2025. In January 2024, WebAssembly was only active during 3.37% of page loads.

WebGPU

WebGPU is the modern successor to WebGL, designed to expose the capabilities of modern GPUs to the web. Unlike WebGL, which was strictly for graphics, WebGPU provides support for compute shaders, allowing for general-purpose computing on graphics cards. This allows developers to perform massive parallel calculations, as required by AI models, directly on the user’s graphics card.

WebGPU has become the standard foundation for running AI workloads in the browser. With the release of Firefox 141 in November 2025, WebGPU became available in all relevant browser engines (Chromium, Gecko, and WebKit).

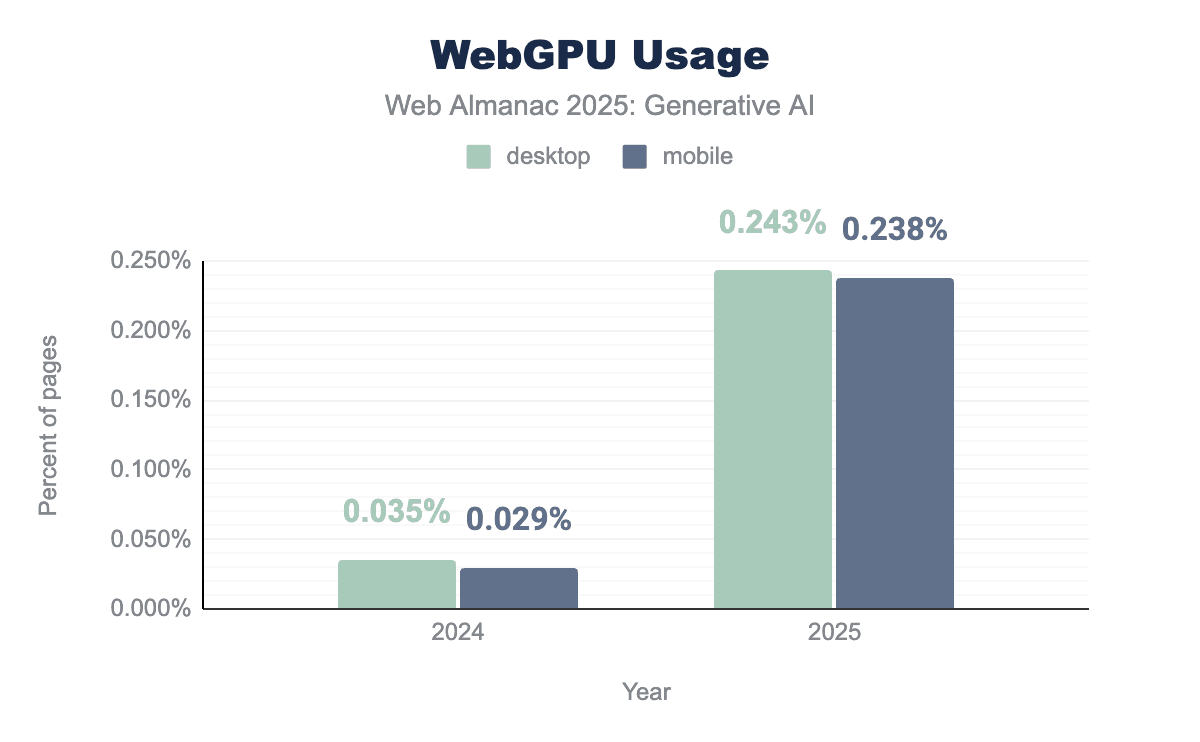

The July 2025 crawl of HTTP Archive data shows that the API is used on 0.243% of all desktop sites and 0.238% of mobile sites. While still small overall, this represents a significant increase of 591% (up from 0.035%) on desktop and 709% (up from 0.029%) on mobile compared to the July 2024 crawl. Chrome Platform Status data suggests an exponential growth in activations per page load, increasing by 147% over the course of 2025.

WebNN

The Web Neural Network API (WebNN) is a dedicated API specifically for machine learning. Specified by the WebML Working Group, this API is on the W3C Recommendation track—the formal process for becoming a web standard.

WebNN serves as a hardware-agnostic abstraction layer, allowing the browser to route operations to the most efficient hardware available on the device. In contrast to WebAssembly (CPU-only) and WebGPU (GPU-only), WebNN can perform computations on the CPU, GPU, and NPU. It can achieve near-native execution speeds.

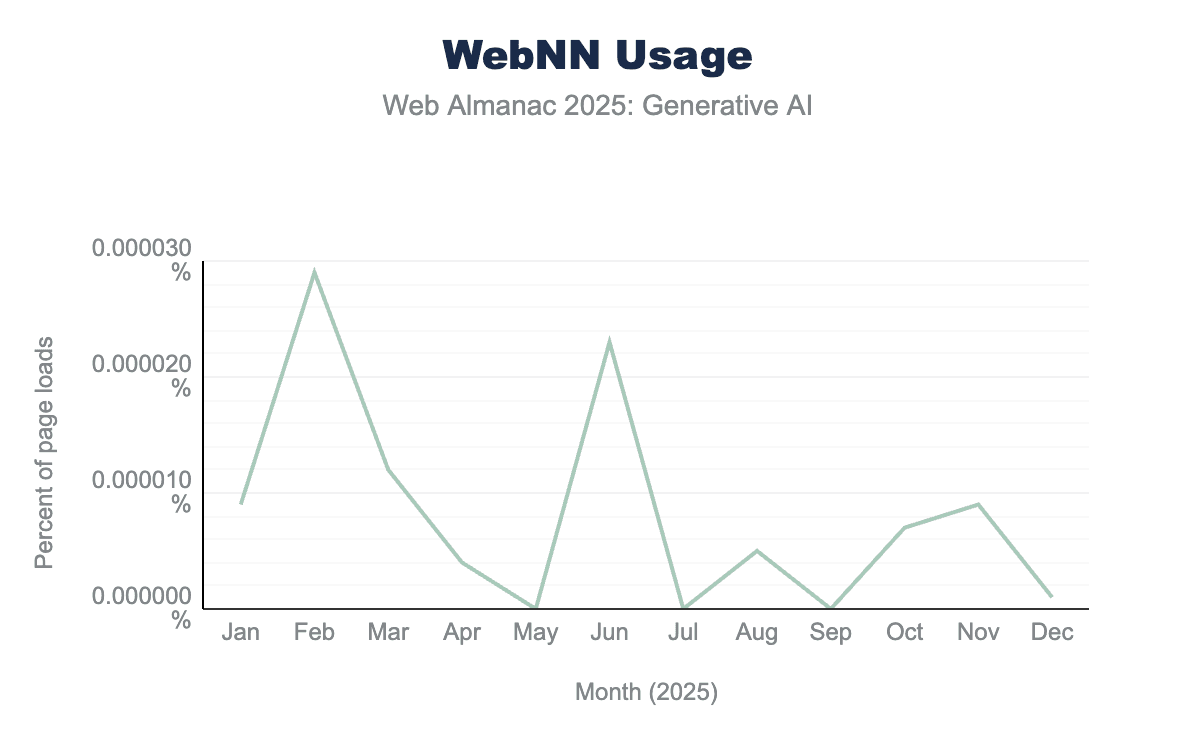

WebNN is in active development and is currently implemented behind a flag in Chromium-based browsers on ChromeOS, Linux, macOS, Windows, and Android. In November 2025, Firefox joined as the second engine formally supporting the API. Given that WebNN is still an experimental API, the usage count is currently very low, with high fluctuation and a maximum activation rate of 0.000029% in February 2025 according to Chrome Platform Status data.

Runtimes: ONNX Runtime and Tensorflow.js

ONNX Runtime (developed by Microsoft) and Tensorflow.js (developed by Google) are two of the leading runtimes for executing AI models directly in the browser. These runtimes abstract away the complexities of low-level technologies like WebAssembly, WebGPU, and WebNN.

TensorFlow.js is tightly integrated with the TensorFlow ecosystem and supports both training and inference, while ONNX Runtime focuses on cross-platform inference using the ONNX standard, enabling models from multiple frameworks to run client-side.

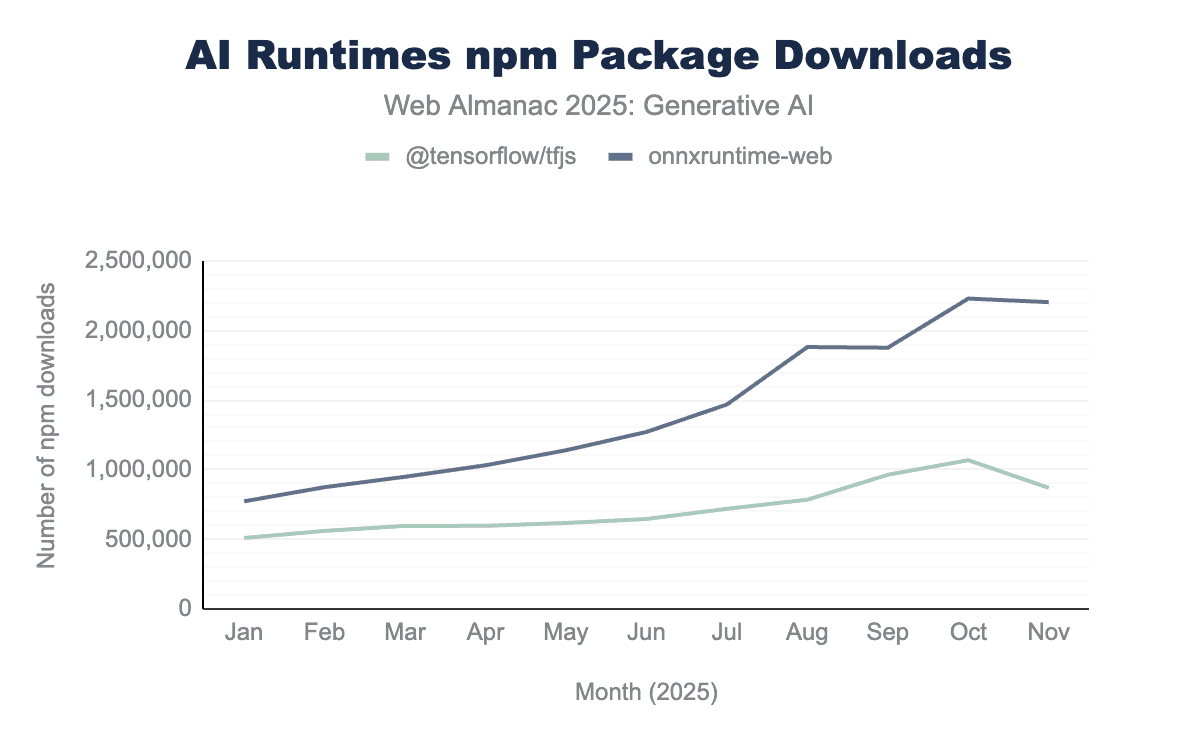

@tensorflow/tfjs and onnxruntime-web.

From January to November 2025, npm package downloads of ONNX Runtime increased by 185%, while TensorFlow.js’s downloads increased by 70%, demonstrating strong and growing developer interest in browser-based AI.

Libraries: WebLLM and Transformers.js

WebLLM, developed by the MLC AI research team, is a high‑performance in‑browser inference engine specialized for LLMs. It allows running various open-weight LLMs, including Llama, Phi, Gemma, or Mistral, directly in the browser. Currently, WebLLM uses WebGPU for inference.

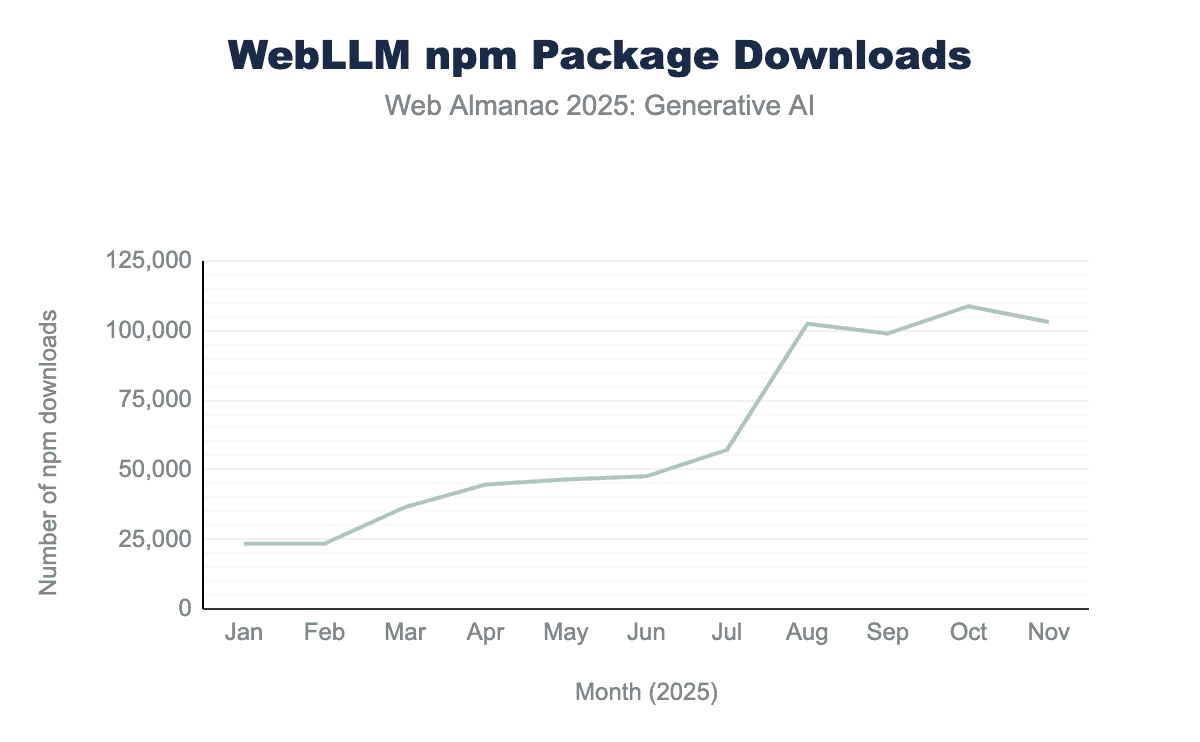

@mlc-ai/web-llm package from January to November 2025. Downloads increased by 340% from 23,425 package downloads in January to 103,084 downloads in November, with a significant spike occurring in August where downloads nearly doubled from 57,114 in July to 102,440 in August.@mlc-ai/web-llm.

WebLLM has quickly become one of the most prominent solutions for in‑browser LLM inference. Between January and November 2025, WebLLM package downloads from npm increased by 340%. In August alone, the downloads numbers nearly doubled. We were unable to attribute this surge to a specific event.

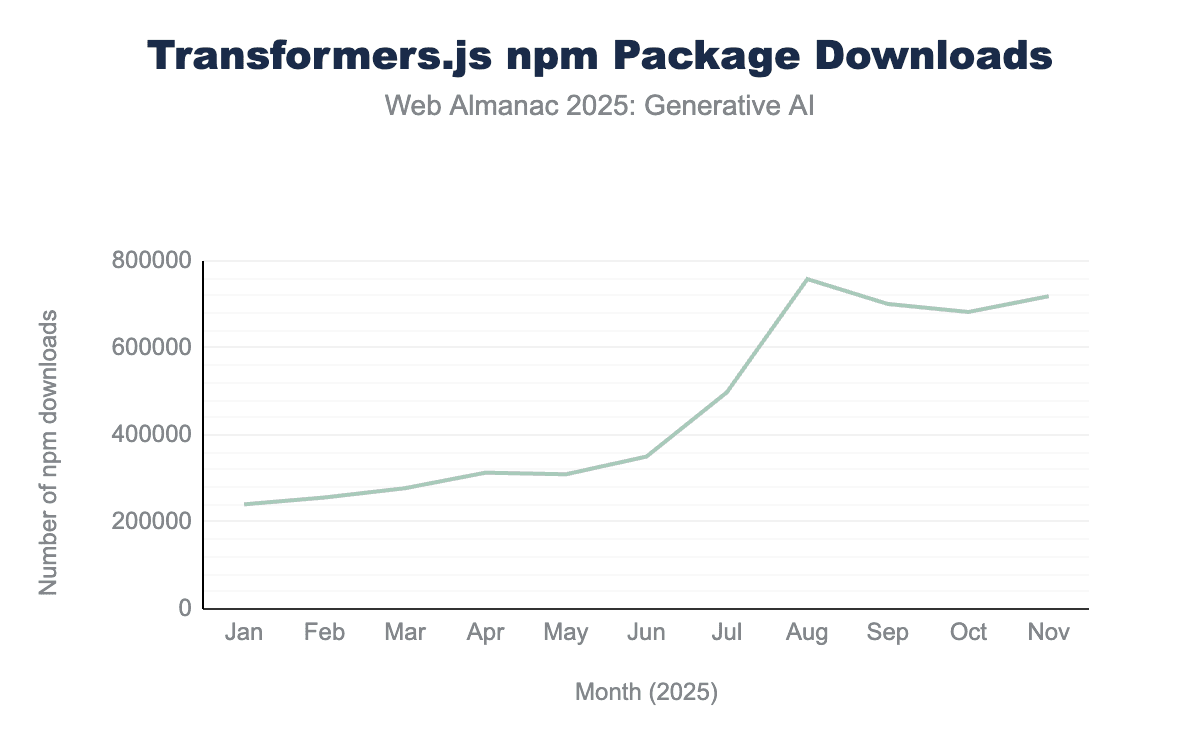

Transformers.js, developed by Hugging Face, functions as a comprehensive JavaScript library that mirrors the popular Python transformers API. Under the hood, it relies on ONNX Runtime to execute. It allows developers to run pre-trained models for various tasks through simple high-level pipelines, not just LLMs.

@huggingface/transformers package from January to November 2025. Downloads nearly tripled from 240,389 in January to 719,103 in November. The trend highlights a significant spike in August, reaching a year-to-date peak of 758,393.@huggingface/transformers.

From January to November 2025, the npm package downloads almost tripled, also with a notable surge in August 2025.

Built-in AI

Built-in AI is an initiative by Google and Microsoft that aims to provide high-level AI APIs to web developers. Unlike BYOAI, this approach leverages models facilitated by the browser itself. While developers cannot specify an exact model, this method allows all websites to share the same model, meaning it only needs to be downloaded once.

The initiative consists of multiple APIs:

- Prompt API: Gives developers low-level access to a local LLM.

-

Task-specific APIs:

- Writing Assistance APIs: Summarizing, writing, and rewriting text.

- Proofreader API: Finding and fixing mistakes in text.

- Language Detector and Translator APIs: Detecting the language of text content and translating it into another language.

All APIs are specified within the WebML Community Group, meaning they are still incubating, and are not yet on the W3C Recommendation track. Some of the APIs are already generally available, while others need a browser flag to be enabled or are in Origin Trial, requiring a registered token for activation—unlike WebGPU, which is now stable and widely available for shipping production features.

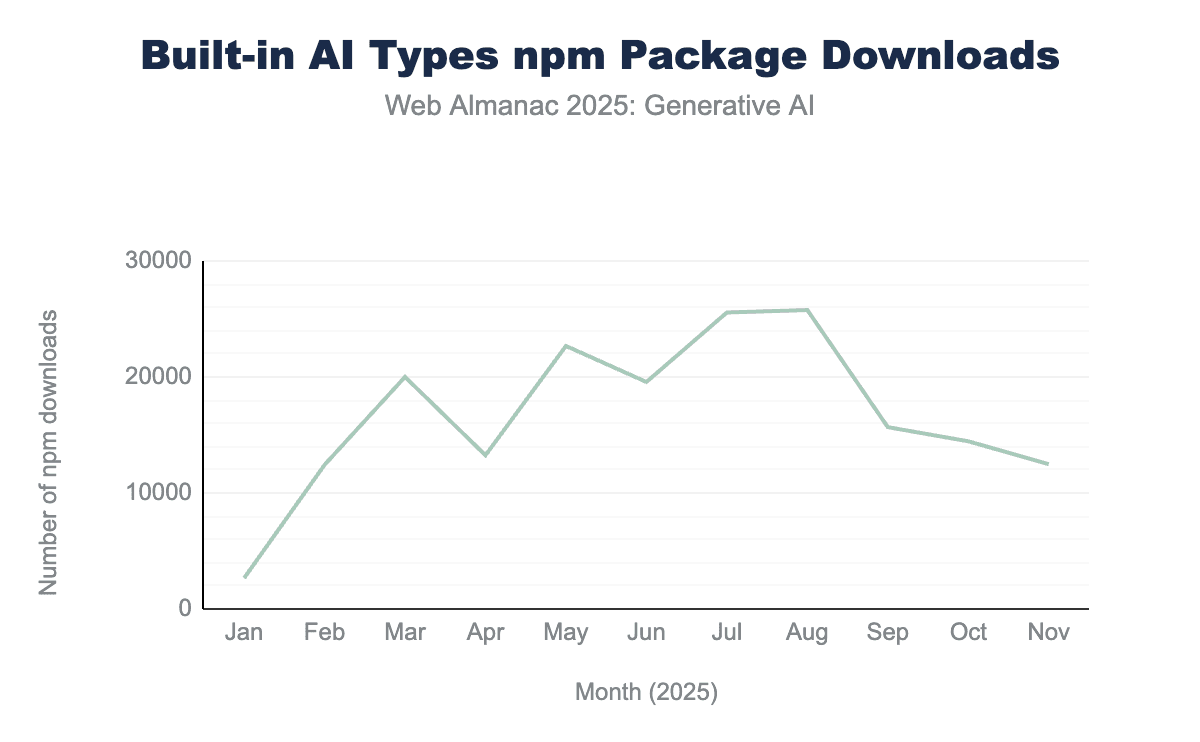

@types/dom-chromium-ai package from January to November 2025. Downloads started at 2,653 in January, peaked at 25,770 in August, and followed a gradual decline to 12,478 in November.@types/dom-chromium-ai.

The download numbers of the @types/dom-chromium-ai package, containing TypeScript typings for Built-in AI, may reflect the experimental status of the APIs: Downloads peaked in August 2025 with 25,770 downloads, followed by a gradual decline. This trend may suggest that developers are hesitant to adopt experimental APIs. However, the download statistics for a typings package may not reflect the actual usage of the API.

Prompt API

The Prompt API introduces a standardized interface for accessing LLMs facilitated by the user’s browser, such as Gemini Nano in Chrome or Phi-4-mini in Edge. By leveraging these one-time-download models, the API eliminates the bandwidth barriers and cold-start latency associated with libraries that require downloading model weights.

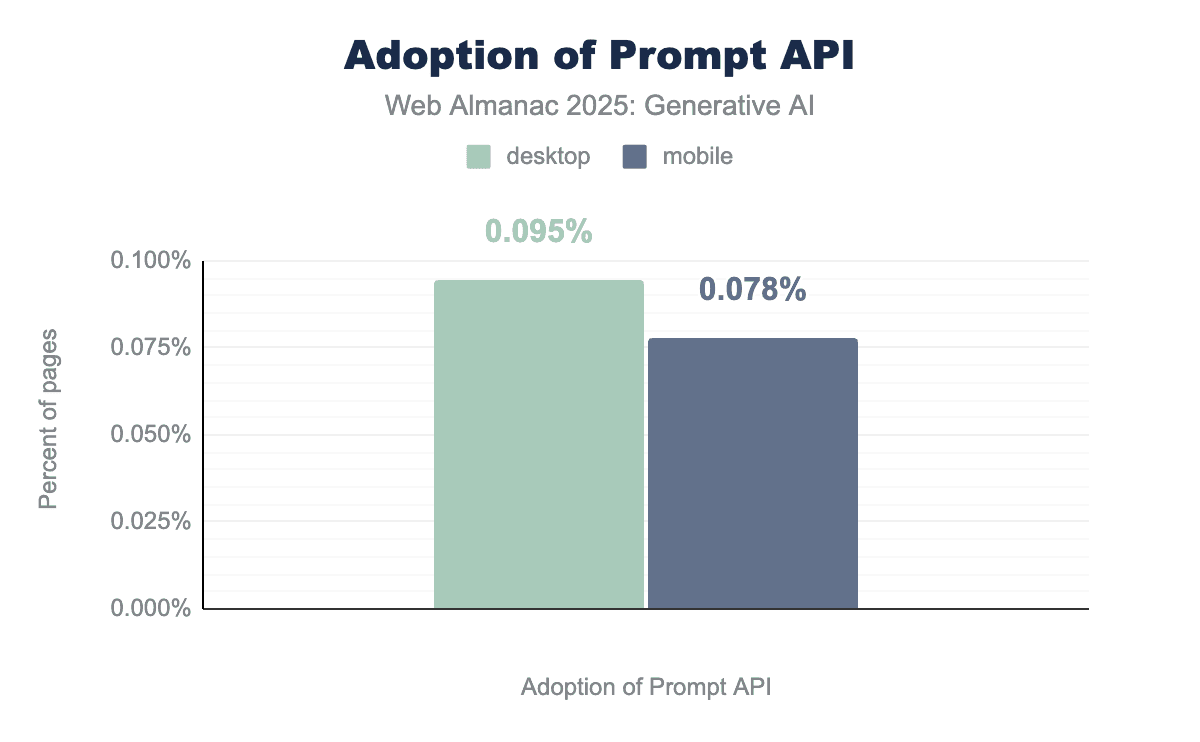

However, as of December 2025, the technology remains in a transitional phase: it has fully shipped for browser extensions in Chrome 138, but web page access is still restricted to an Origin Trial. The API is not currently available on mobile devices.

Consequently, adoption remains nascent; HTTP Archive data from July 2025 (the first measurement available) detected the API on just 0.095% of all desktop sites and 0.078% of all mobile sites, reflecting its current status as an experiment rather than a standard utility.

Most of the example sites we analyzed used the Prompt API through an external script, Google Publisher Tags. This project enables authors to incorporate dynamic advertisements into their websites. The Google Publisher Tags script uses the Prompt API to categorize the page’s content into a list of the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) Content Taxonomy 3.1 categories, and the Summarizer API (see next section) to generate a summary of the page’s content, and sends both to the server. However, the code branch didn’t seem to be active during our analysis.

Writing Assistance APIs and Proofreader API

Next, we examine the task-specific APIs. The Writing Assistance APIs abstract the complexities of prompt engineering; they utilize the same underlying embedded LLM but apply specialized system prompts to achieve distinct linguistic goals:

- Writer API: creates new content based on a prompt

- Rewriter API: rephrases input based on a prompt

- Summarizer API: produces a summary of text

Additionally, the Proofreader API enables developers to proofread text and correct grammatical errors and spelling mistakes.

The Summarizer API shipped with Chrome 138. As of December 2025, the Writer, Rewriter, and Proofreader API are in Origin Trial. All APIs are not currently available on mobile devices.

In the July 2025 HTTP Archive crawl, only calls to Writer.create() were detected (on 0.127% desktop and 0.137% mobile sites). While this initially suggested usage of the Writer API, manual checks revealed that many sampled sites were actually using Protobuf.js’s Writer, which shares the same API signature. As a result, we have decided to omit the chart for this metric.

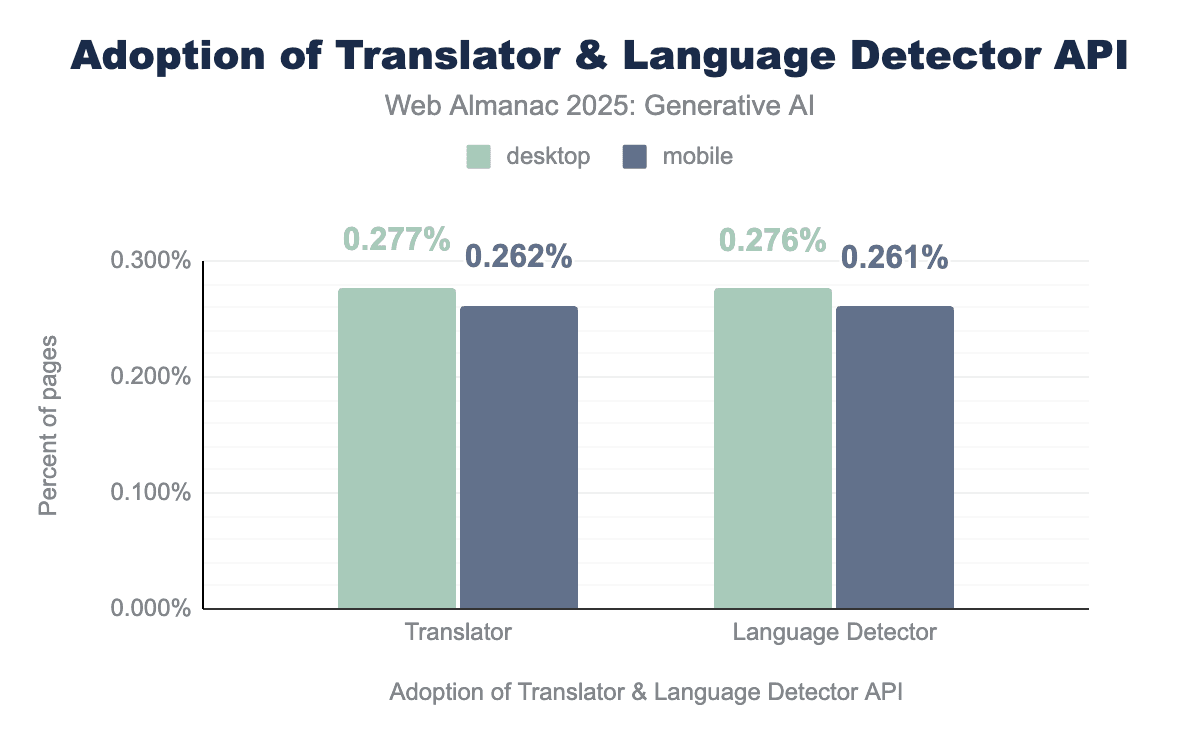

Translator and Language Detector APIs

The final category of the Built-in AI APIs consists of the Translator and Language Detector APIs. Unlike the Writing Assistance APIs, these APIs do not rely on LLMs, but instead utilize specialized, task-specific neural networks, placing them outside the strict definition of Generative AI.

The APIs shipped in Chrome 138 but are not currently available on mobile devices.

They have achieved the widest adoption of the Built-in AI APIs. The July 2025 HTTP Archive crawl detected the Translator API on 0.277% of all desktop sites and 0.262% of all mobile sites, with the Language Detector API used on just 0.001% fewer sites.

Many of the sample sites we checked utilized the review tool Judge.me, which serves as an add-on for Shopify stores. Judge.me utilizes both the Language Detector and Translator APIs, which may be the reason for the tight coupling of usage: The Language Detector API was present on nearly the same absolute number of sites, trailing the Translator API by only approximately 100 sites.

Browser-specific runtimes: Firefox AI Runtime

As an alternative to the Built-in AI APIs proposed by the Chromium side, Firefox experiments with the Firefox AI Runtime, a local inference runtime based on Transformers.js and the ONNX Runtime, which runs natively. However, the runtime is not yet accessible from the public web. It can only be used by extensions and other privileged uses, such as the built-in translation feature of Firefox.

Discoverability

In this section, we look at the dynamics of web discoverability with increasing adoption of Generative AI on the web. We primarily focus on two important approaches that influence how AI platforms and services discover content: the robots.txt and llms.txt files.

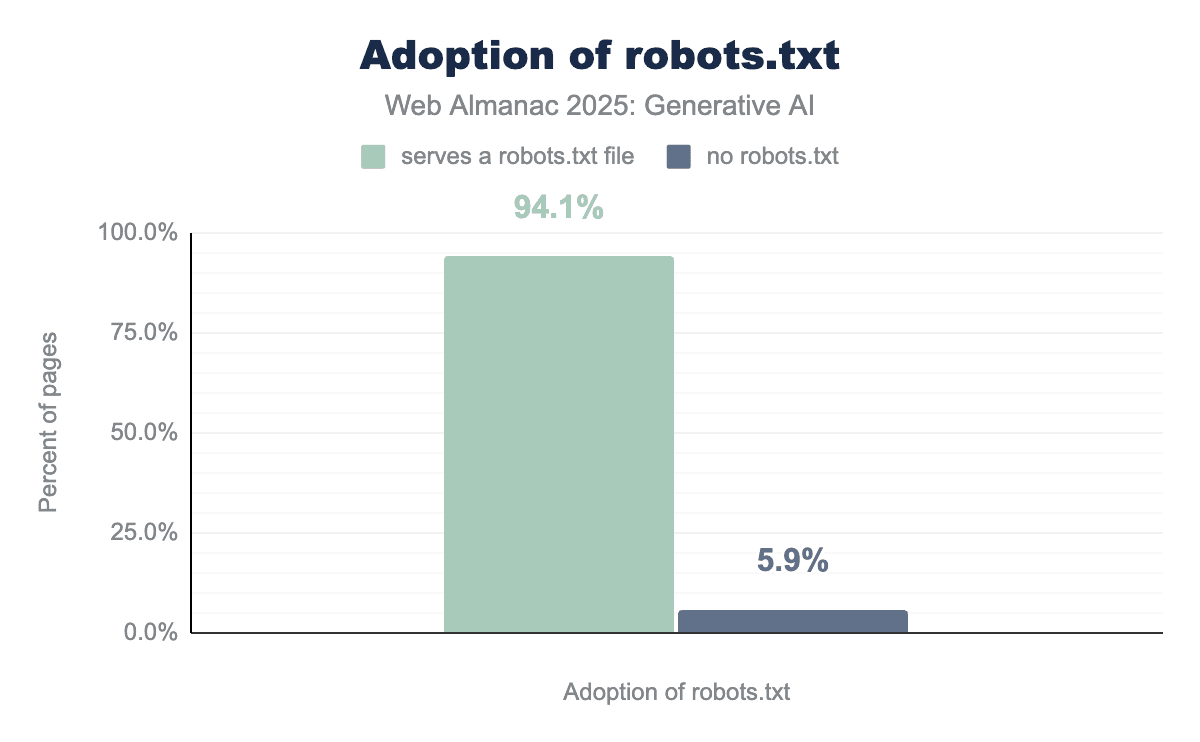

robots.txt

The robots.txt file, located at the root of a domain (for example, http://example.com/robots.txt), allows website owners to declare crawl directives for automated bots. Historically, web crawling was primarily performed by search engines and archives. However, in the age of Generative AI, websites can also be crawled by AI agents, or by model providers collecting internet-scale data to train their LLMs. Consequently, websites increasingly rely on robots.txt files to manage access for these crawlers.

An example directive targeting the user agent GPTBot, used by OpenAI for model training, is shown below:

User-Agent: GPTBot

Disallow: /It is important to note that adherence to robots.txt is voluntary and does not strictly enforce access control.

robots.txt. A significant 94.1% of sites serve the file.robots.txt adoption.

Usage of robots.txt remains highly prevalent: approximately 94.1% of the ~12.9 million sites analyzed include a robots.txt file with at least one directive.

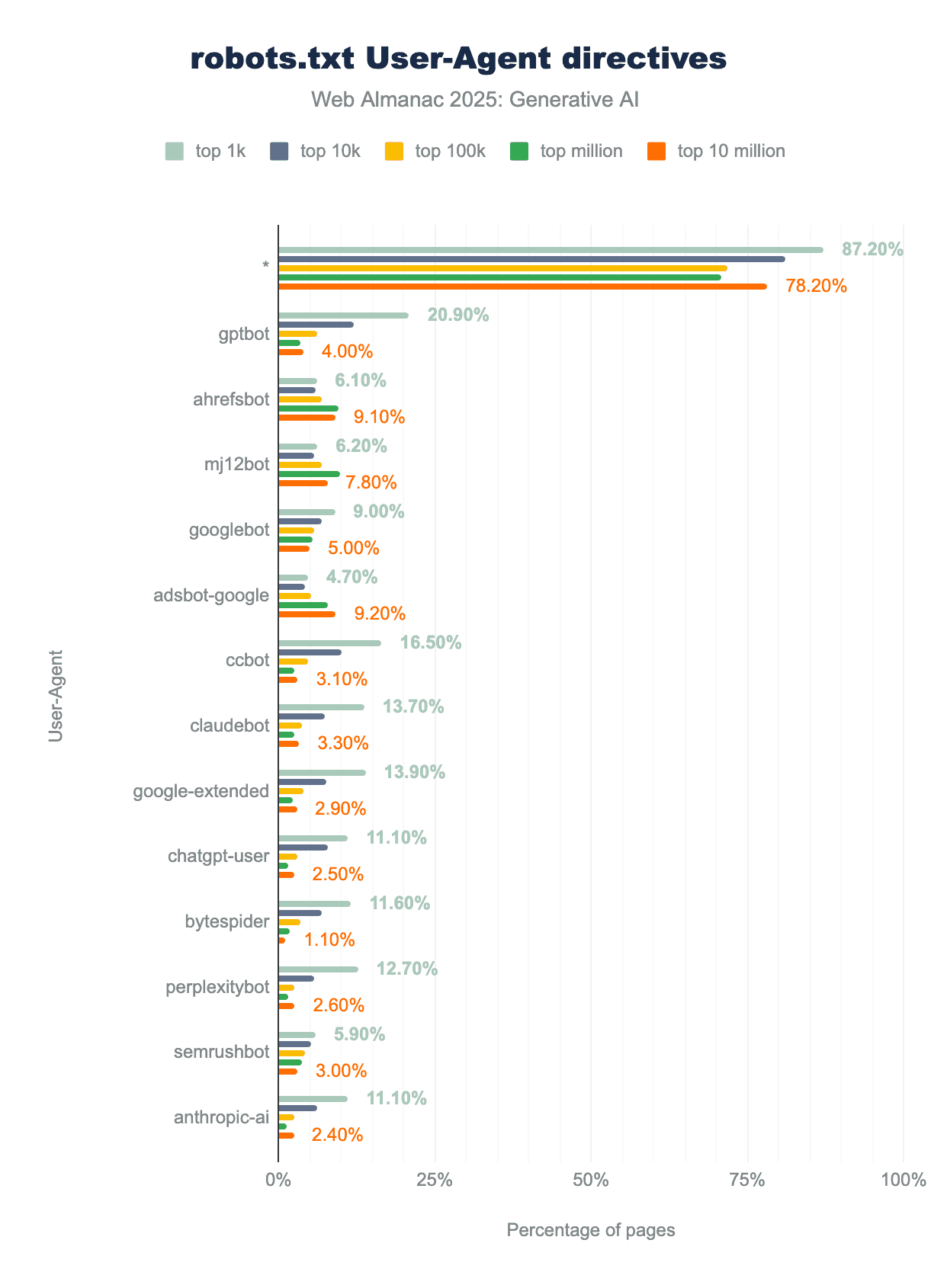

robots.txt User-Agent directives by site rank. The wildcard * is the most common directive, followed by the gptbot directive. The next AI bot, claudebot, is on eighth position. Top 1k sites tend to mention bots more often than less popular sites. For example, gptbot is mentioned in the robots.txt file of 20.9% of top 1k sites, 12.1% of top 10k sites, 6.1% of top 100k sites, 3.6% of top 1 million sites, and 4% of top 10 million sites.robots.txt directives by website ranks.

The figure above shows the top directives observed across all websites, grouped by their rank. The wildcard directive * is the most commonly used one, present in 97.4% of robots.txt files. It allows site authors to set global rules for all bots. The second most used user agent is gptbot (note, our analysis lower-cased the user-agent names), which saw adoption rise from 2.6% in 2024 to around 4.5% in 2025.

Other frequently targeted AI bots include those from Anthropic (claudebot, anthropic-ai, claude-web), Google (google-extended), OpenAI (chatgpt-user), and Perplexity (perplexitybot).

Directives targeting AI bots are significantly more common on popular websites, with nearly all of them disallowing access. This is likely because popular websites can restrict AI crawlers without negatively impacting their organic traffic. Overall, we observed a clear increase in the adoption of AI-specific directives within robots.txt files.

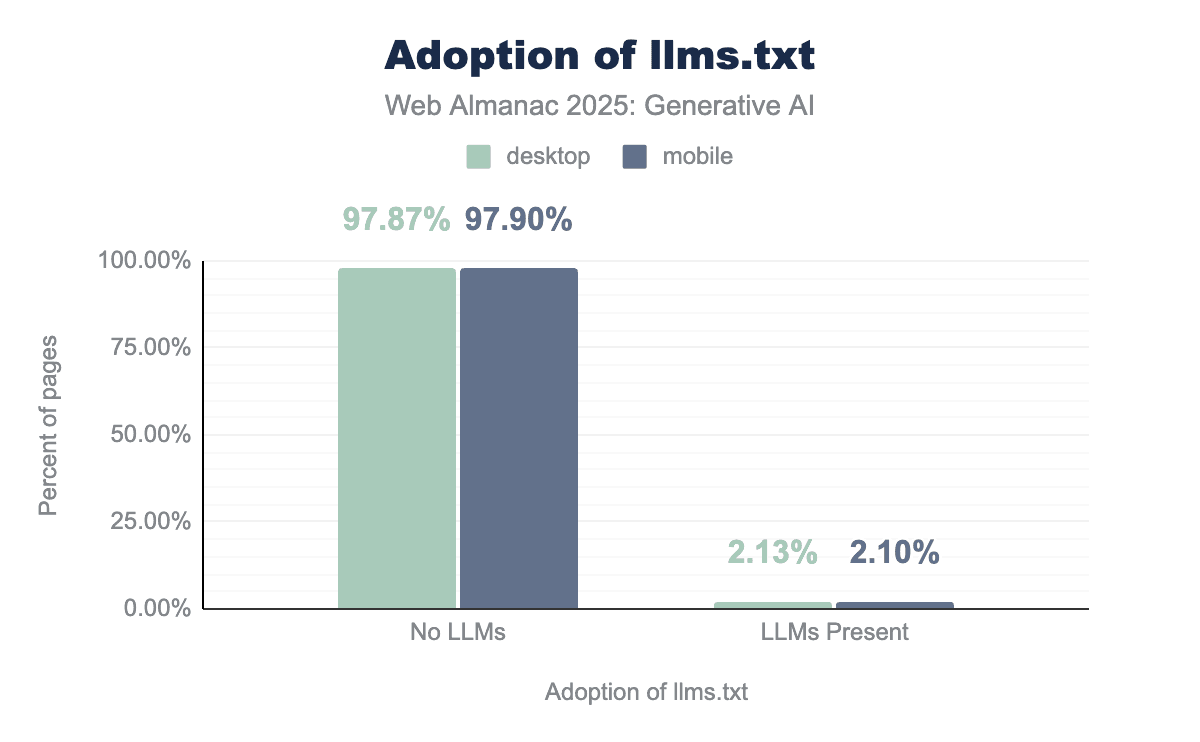

llms.txt

The llms.txt file is an emerging proposal designed to help LLMs effectively utilize a website at inference time. Similar to robots.txt, it is hosted at the root of a website’s domain (for example, https://example.com/llms.txt). The key distinction lies in their function: while robots.txt instructs bots as to what they are allowed or disallowed to crawl during training or inference, llms.txt provides a structured, LLM-friendly overview of the website’s content. This allows LLMs to efficiently navigate through a website in real-time when answering user queries.

llms.txt. The file is only present on 2.13% of desktop and 2.1% of mobile sites, and absent on the vast majority of 97.87% desktop and 97.9% of mobile sites.llms.txt adoption.

As llms.txt is relatively new, we observed very limited usage on the web. Across desktop pages, only 2.13% exhibit valid llms.txt entries, while 97.87% show no evidence of this file. Mobile pages showed a similar pattern, with 2.1% of pages containing valid entries and 97.9% lacking them.

The overwhelming majority of sites therefore do not yet articulate explicit AI access preferences via llms.txt. Where present, the file indicates that early adopters are likely experimenting with AI-driven discoverability, facilitating agentic use cases, or exploring Generative Engine Optimization (GEO). In contrast to Search Engine Optimization (SEO), GEO focuses on making content easily ingestible by LLMs or AI-enabled search tools like Perplexity or Google AI Mode. For more information see the SEO chapter.

AI fingerprints

Services such as OpenAI ChatGPT, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot are already widely used. Increasingly, content is being written with the assistance of AI. This section analyzes the impact of Generative AI on web content and source code.

AI colors

Models can tend to overrepresent certain words, which then serve as an AI fingerprint. Researchers at Florida State University compared research papers published on PubMed between 2020 and 2024. Their analysis revealed a staggering 6,697% increase in the use of the word “delves.” The other conjugations of the verb “delve” also increased significantly. While those kinds of indicators should never be used to classify individual cases as AI-generated, they are still useful for understanding the trend of adoption. In this part of the chapter, we will delve into ;) common patterns used by LLMs to generate websites.

The most recognizable indicator of AI-generated web design is the pervasive use of purple and gradients, often referred to as “the AI Purple Problem.”

Adam Wathan, creator of the widely adopted CSS framework Tailwind, noted in a recent interview that this trend likely stems from the timing of major AI training crawls. In the early 2020s, the Tailwind team used deep purples extensively in their documentation and examples to reflect contemporary design trends. Consequently, LLMs trained on that data seem to have “locked in” an aesthetic that has since been replaced by more modern trends, such as the current preference for black designs.

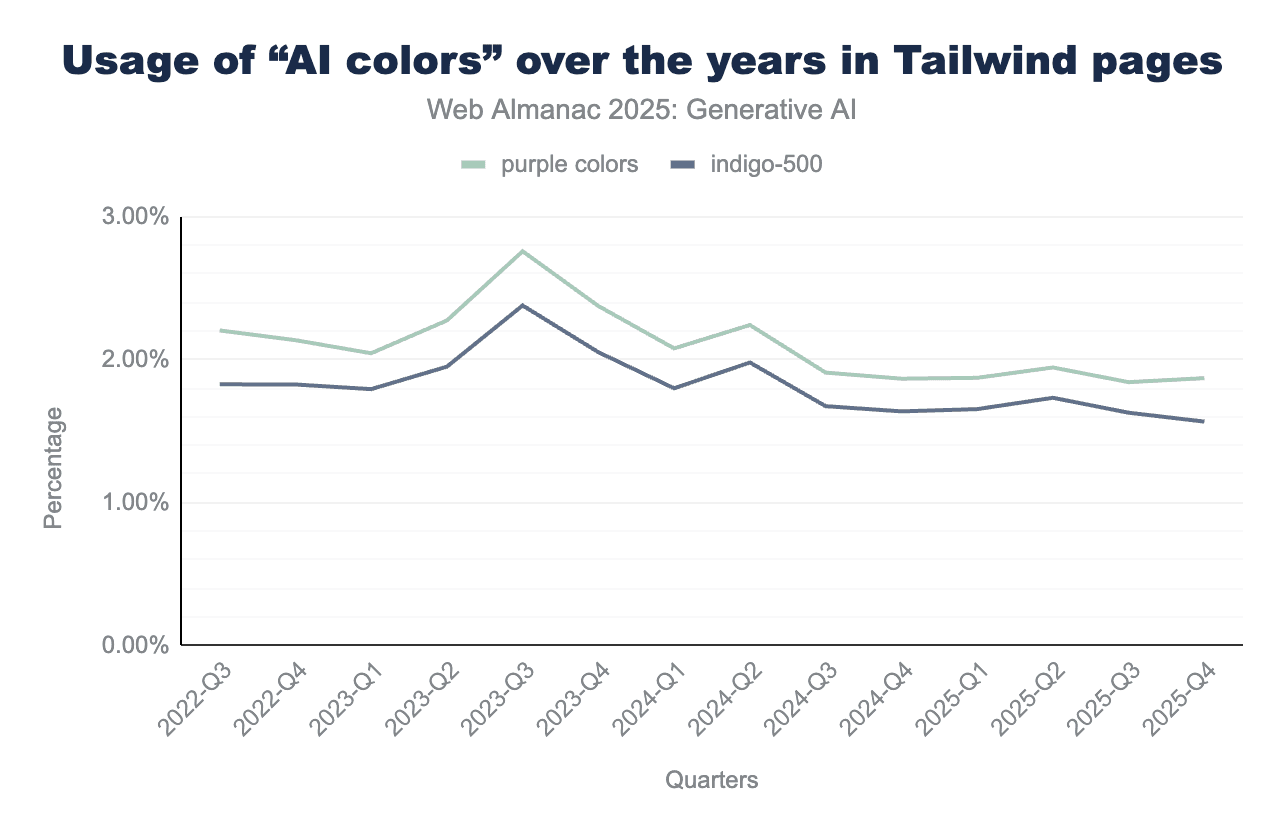

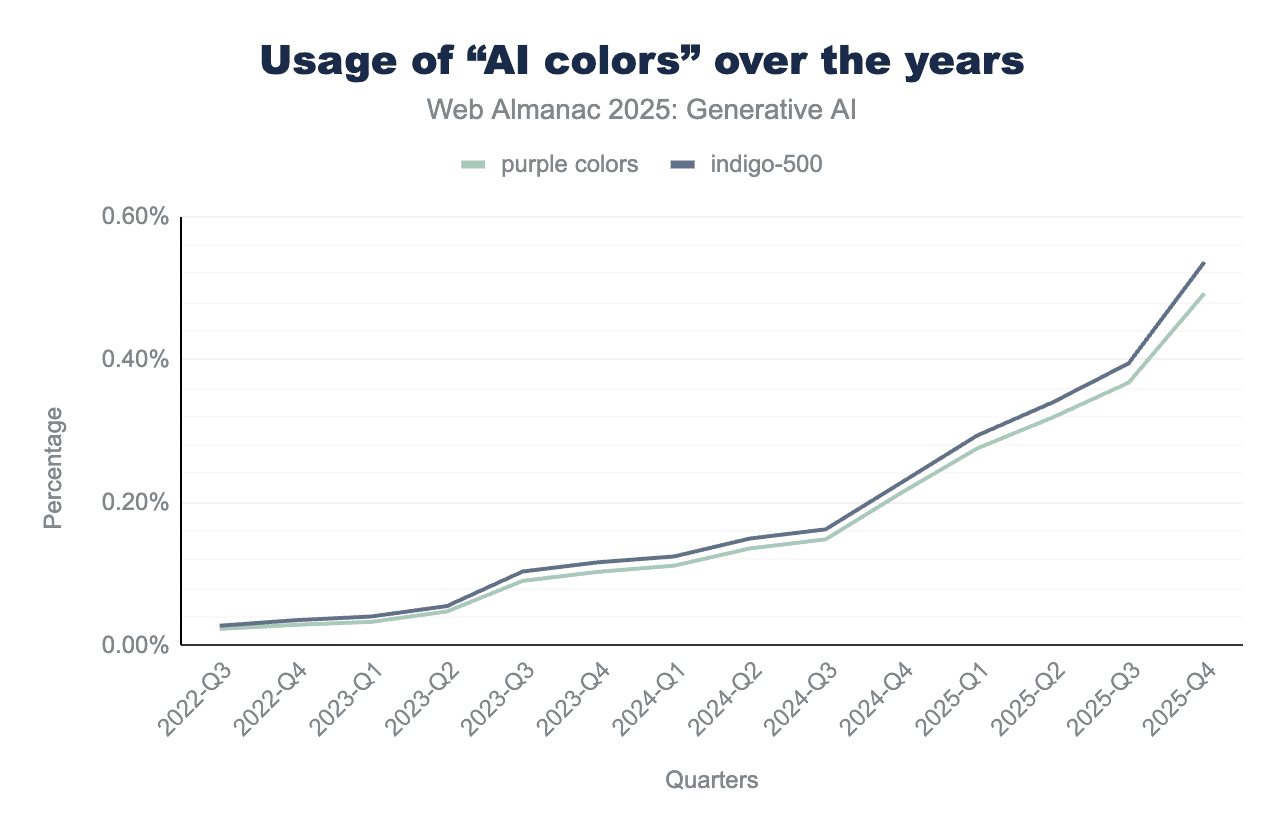

To quantify the “AI Purple” aesthetic, we analyzed the CSS (responsible for website styling) of all root pages in our dataset from the years following the release of ChatGPT. We tracked the presence of the well-known indigo-500 color (#6366f1), the use of CSS gradients, and other colors associated with AI-generated websites.

Because Tailwind is the preferred framework for LLMs like Claude, Gemini, and the OpenAI models, we specifically examined the percentage of Tailwind-based websites using these indicators. Tailwind web pages were identified using a Wappalyzer fork from the HTTP Archive. Surprisingly, there was no noticeable surge in websites using either indigo-500 or the other two commonly mentioned AI colors (#8b5cf6 violet and #a855f7 purple).

However, due to the explosive overall growth of the Tailwind framework, these specific colors saw a significant rise when measured as a percentage of the entire web.

Our analysis relied solely on CSS variables, as parsing the entire source code would exceed practical limits. As a result, our figures represent a conservative estimate. Sites using hardcoded hex values (for example, #6366f1) or older preprocessors were invisible to our queries. Additionally, even a 1% adjustment to a color’s lightness would cause it to evade our detection.

Despite the frequent online discourse regarding “AI slop” and purple-tinted designs, our analysis of the HTTP Archive dataset suggested that this trend may be less a result of AI “choosing” purple and more a reflection of the general rise in Tailwind’s popularity.

We also tested for surges in gradients, shadows, and specific fonts, but found no statistically significant increases.

Vibe coding platforms

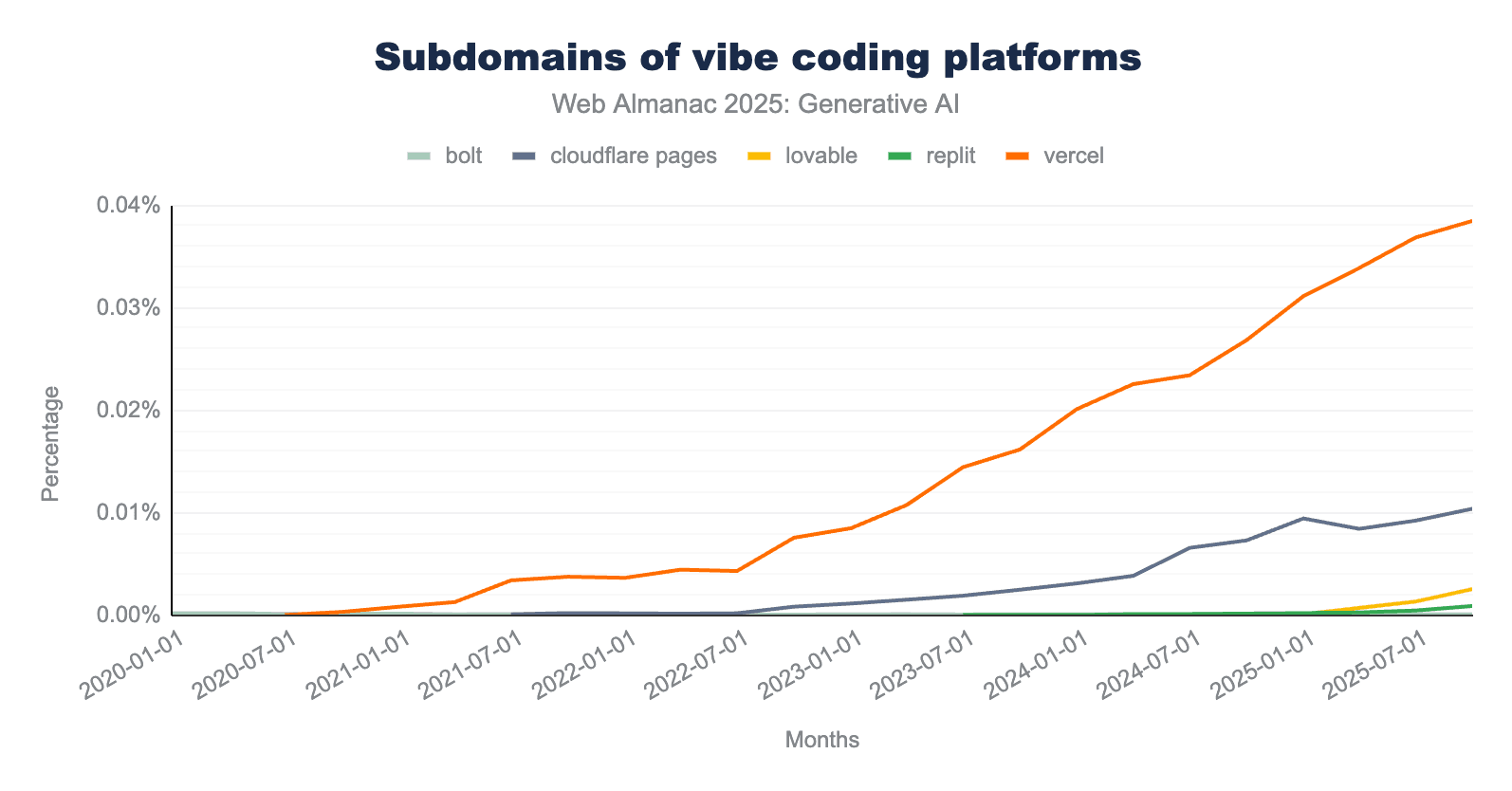

One of the reasons for the large number of newly created websites is the emergence of platforms that make building them easier. After the spread of Content Management System (CMS) tools in the previous decade, users can now move beyond those guardrails and use tools like v0, Replit, or Lovable to generate websites through conversational AI. These platforms allow users to publish pages using their own domains or a platform-provided subdomain (for example, mywebsite.tool.com).

The chart above illustrates the relative growth of vibe coding platform subdomains within the HTTP Archive dataset. While Vercel (*.vercel.app) remains the dominant provider, it has offered subdomain hosting long before the release of its vibe coding tool v0 (*.v0.dev) in late 2023. The data showed no immediate surge following the launch of v0. Lovable (*.lovable.app and *.lovable.dev) grew from only 10 subdomains at the beginning of 2025 to 315 by October 2025. Please note that this only includes pages available in the dataset. According to Lovable, 100,000 new projects are built on Lovable every single day.

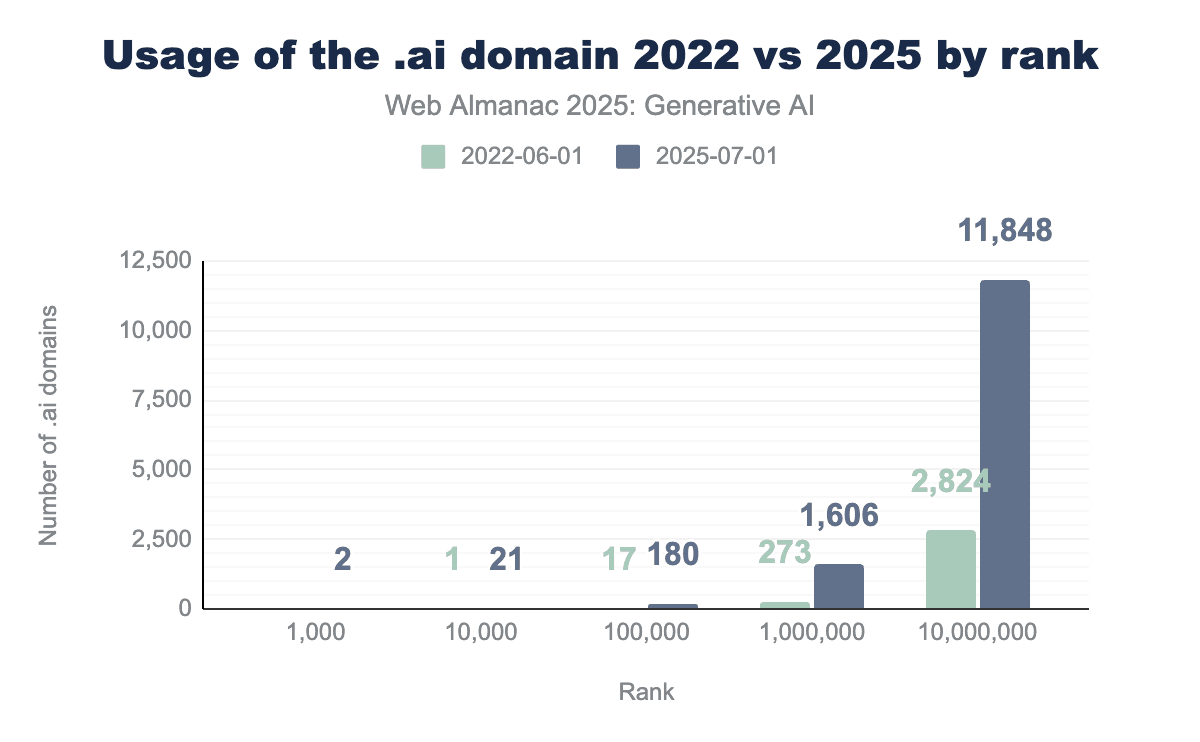

The .ai domain

While both AI and the .ai domain existed long before ChatGPT, the new possibilities that emerged in its wake led to a wave of AI-native businesses. Many of them adopted the .ai top-level domain, the country code for Anguilla. This trend drove a substantial rise in .ai domain registrations across all ranks, as shown in the figure above, which compares the pre-ChatGPT landscape in 2022 with usage in 2025.

The only two .ai domains that made it into the top 1,000 most visited websites in the Chrome dataset were https://character.ai and an adult site.

Conclusion

In 2025, Generative AI transitioned from a cloud-only technology to a fundamental browser component. BYOAI dominated immediate adoption, driven by the growth of foundational APIs, such as WebAssembly and WebGPU, as well as libraries like WebLLM and Transformers.js. At the same time, Built-in AI began laying the groundwork for a standardized AI layer directly within the browser. A tension has formed between more restrictive robots.txt files and the welcoming structure of llms.txt. The rise of vibe coding and .ai domains proves that AI isn’t just reshaping how apps function, but also how they are built.

Looking beyond 2025, the next evolutionary leap is already visible: Agentic AI. We are moving away from the era of interactive chatbots toward autonomous agents that are capable of making decisions, executing multi-step workflows, and solving complex tasks without continuous user intervention. This shift is giving rise to a new class of “agentic browsers” such as Perplexity Comet, ChatGPT Atlas, or Opera Neon.

To connect these agents to the vast resources of the web, new protocols such as WebMCP (Web Model Context Protocol) are emerging. Just as HTTP standardizes the transmission of resources, WebMCP aims to standardize the way agents perceive and manipulate web interfaces, ensuring that the AI-native web is not only readable but also actionable.